Page Object Model: Building Maintainable Test Automation

Quick summary: Page Object Model centralizes UI interactions in one place instead of hunting through hundreds of test files. Proper architecture with organized directories, reusable components, and clean abstractions prevents maintenance nightmares. Code quality matters in tests (DRY principles, single responsibility, descriptive naming). Over-abstraction is real, small projects don't need elaborate frameworks.

Introduction

Friday afternoon. You push a small UI change, a designer moved the login button 20 pixels to the right. Harmless, right?

Monday morning. Fifty tests are failing. None of them found real bugs. Every single failure is because your tests can't find the login button anymore. You spend three days updating hardcoded selectors across dozens of test files.

Tuesday. Another designer change. Another wave of broken tests.

This is test automation hell. Page Object Model is how you escape it.

Page Object Model (POM) isn't just a pattern, it's the difference between maintainable tests and technical debt that crushes your team. When one UI change breaks fifty tests, you don't have a UI problem. You have an architecture problem.

This guide shows you how to build test automation that survives UI changes, scales with your application, and doesn't require a full-time engineer just to keep tests running.

You can follow this guide with code examples with this GitHub repository.

What is Page Object Model?

Page Object Model is a design pattern where each page or component in your application becomes a class. That class encapsulates all interactions with that page, element locators, actions you can perform, and data you can retrieve.

Instead of writing this in every test:

// Brittle: Selectors scattered everywhere

await page.fill('#username', 'testuser');

await page.fill('#password', 'testpass123');

await page.click('.login-btn');

await expect(page.locator('.dashboard-header')).toBeVisible();You write this:

// Maintainable: Selectors centralized in LoginPage class

await loginPage.login('testuser', 'testpass123');

await expect(dashboardPage.header).toBeVisible();When the designer changes #username to [data-test="username-input"], you update one place: the LoginPage class. Every test using that page object automatically works.

The Problem POM Solves

I watched a QA team maintain 300 automated tests. A designer renamed CSS classes during a rebrand. Every test referenced those classes directly.

Result: 287 test failures. Zero real bugs. The QA lead spent a full week updating selectors. She told me: "Every sprint. We budget two days per sprint for 'fixing tests that aren't broken.'"

That's 104 days per year maintaining tests instead of testing new features.

Without POM, tests become spaghetti code. The checkout button selector appears in 23 different test files. When it changes, you update 23 files. Miss one? Broken test. Every login flow is duplicated across dozens of tests with hardcoded selectors.

With POM, tests become readable. You update CartPage.proceed_to_checkout() once. Twenty-three tests immediately work again.

Building a Scalable Test Structure

Here's how to organize test automation that doesn't collapse under its own weight.

test-automation/

├── pages/

│ ├── base_page.py # Base class with common methods

│ ├── login_page.py # Login page object

│ └── checkout_page.py # Checkout page object

├── components/

│ ├── navigation.py # Reusable navigation component

│ └── modal.py # Generic modal component

├── tests/

│ ├── test_authentication.py

│ └── test_checkout.py

├── utils/

│ ├── wait_helpers.py # Custom wait utilities

│ └── data_generators.py # Test data creation

├── config/

│ └── settings.py # Environment configuration

└── requirements.txt

This structure separates concerns. Tests focus on scenarios. Pages handle UI interactions. Components handle reusable elements. Utilities provide cross-cutting functionality.

Base Page: The Foundation

Every page object inherits from a base class containing common functionality.

TypeScript Example:

// pages/BasePage.ts

import { Page, Locator } from '@playwright/test';

export class BasePage {

protected page: Page;

constructor(page: Page) {

this.page = page;

}

async navigateTo(url: string): Promise<void> {

await this.page.goto(url);

}

async click(locator: string): Promise<void> {

await this.page.click(locator);

}

async fill(locator: string, text: string): Promise<void> {

await this.page.fill(locator, text);

}

async getText(locator: string): Promise<string> {

return await this.page.textContent(locator) || '';

}

async isVisible(locator: string): Promise<boolean> {

try {

await this.page.waitForSelector(locator, { state: 'visible', timeout: 10000 });

return true;

} catch {

return false;

}

}

getLocator(selector: string): Locator {

return this.page.locator(selector);

}

}

LoginPage: A Complete Example

Here's a real-world page object implementation.

TypeScript:

// pages/LoginPage.ts

import { Page } from '@playwright/test';

import { BasePage } from './BasePage';

export class LoginPage extends BasePage {

// Locators

private readonly usernameInput = '[data-test="username"]';

private readonly passwordInput = '[data-test="password"]';

private readonly loginButton = '[data-test="login-button"]';

private readonly errorMessage = '.error-message';

private readonly url = '/login';

constructor(page: Page, private baseUrl: string) {

super(page);

}

async navigate(): Promise<void> {

await this.navigateTo(`${this.baseUrl}${this.url}`);

}

async login(username: string, password: string): Promise<void> {

await this.fill(this.usernameInput, username);

await this.fill(this.passwordInput, password);

await this.click(this.loginButton);

}

async getErrorMessage(): Promise<string> {

return await this.getText(this.errorMessage);

}

async isErrorDisplayed(): Promise<boolean> {

return await this.isVisible(this.errorMessage);

}

}Python:

# pages/login_page.py

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By

from pages.base_page import BasePage

class LoginPage(BasePage):

# Locators

USERNAME_INPUT = (By.ID, "username")

PASSWORD_INPUT = (By.ID, "password")

LOGIN_BUTTON = (By.CSS_SELECTOR, "[data-test='login-button']")

ERROR_MESSAGE = (By.CLASS_NAME, "error-message")

URL = "/login"

def __init__(self, driver, base_url):

super().__init__(driver)

self.base_url = base_url

def navigate(self):

self.navigate_to(f"{self.base_url}{self.URL}")

def login(self, username, password):

self.type_text(self.USERNAME_INPUT, username)

self.type_text(self.PASSWORD_INPUT, password)

self.click(self.LOGIN_BUTTON)

def get_error_message(self):

return self.get_text(self.ERROR_MESSAGE)

def is_error_displayed(self):

return self.is_displayed(self.ERROR_MESSAGE)Notice the pattern: selectors are constants at the top. Methods provide semantic actions. Tests never see raw selectors.

Clean Tests Using Page Objects

With page objects in place, tests become declarative and readable.

TypeScript Test:

// tests/authentication.spec.ts

import { test, expect } from '@playwright/test';

import { LoginPage } from '../pages/LoginPage';

import { DashboardPage } from '../pages/DashboardPage';

test.describe('Authentication', () => {

let loginPage: LoginPage;

let dashboardPage: DashboardPage;

test.beforeEach(async ({ page }) => {

loginPage = new LoginPage(page, process.env.BASE_URL || 'http://localhost:3000');

dashboardPage = new DashboardPage(page);

});

test('successful login with valid credentials', async () => {

await loginPage.navigate();

await loginPage.login('testuser@example.com', 'ValidPassword123!');

expect(await dashboardPage.isHeaderDisplayed()).toBe(true);

expect(await dashboardPage.getPageTitle()).toContain('Dashboard');

});

test('error message shown for invalid credentials', async () => {

await loginPage.navigate();

await loginPage.login('invalid@example.com', 'WrongPassword');

expect(await loginPage.isErrorDisplayed()).toBe(true);

expect(await loginPage.getErrorMessage()).toContain('Invalid credentials');

});

});These tests read like documentation. No selectors. No implementation details. Just clear intent.

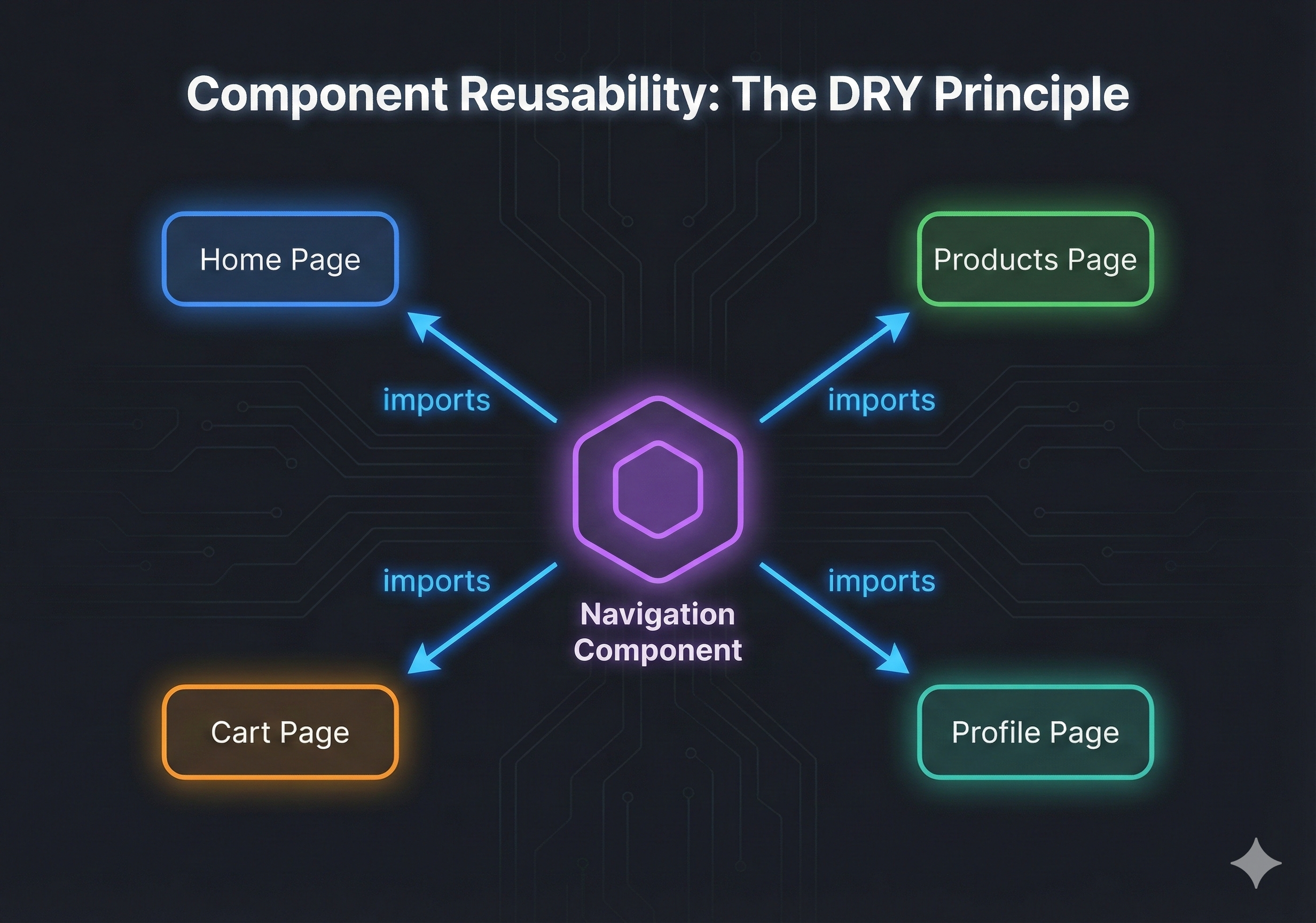

Reusable Components

Many UI elements appear across multiple pages. Navigation menus, modals, forms, these should be separate components.

Navigation Component Example:

// components/Navigation.ts

import { BasePage } from '../pages/BasePage';

export class NavigationComponent extends BasePage {

private readonly homeLink = '[data-nav="home"]';

private readonly productsLink = '[data-nav="products"]';

private readonly cartIcon = '[data-nav="cart"]';

private readonly userMenu = '[data-nav="user-menu"]';

async goToHome(): Promise<void> {

await this.click(this.homeLink);

}

async goToProducts(): Promise<void> {

await this.click(this.productsLink);

}

async openCart(): Promise<void> {

await this.click(this.cartIcon);

}

async isUserLoggedIn(): Promise<boolean> {

return await this.isVisible(this.userMenu);

}

}Any page object can now include navigation. One navigation change updates everywhere instantly.

Configuration Management

Different environments need different configurations. Hardcoding values is brittle.

Configuration File:

# config/settings.py

import os

class Config:

ENV = os.getenv("TEST_ENV", "dev").lower()

URLS = {

"dev": "http://localhost:3000",

"staging": "https://staging.example.com",

"production": "https://example.com"

}

BROWSER = os.getenv("BROWSER", "chrome")

HEADLESS = os.getenv("HEADLESS", "false").lower() == "true"

DEFAULT_TIMEOUT = int(os.getenv("DEFAULT_TIMEOUT", "10"))

@classmethod

def get_base_url(cls):

return cls.URLS.get(cls.ENV, cls.URLS["dev"])Run tests against different environments:

# Run against staging

TEST_ENV=staging pytest tests/

# Run headless in CI

HEADLESS=true pytest tests/Clean Code Principles for Tests

Tests are code. They deserve the same quality standards as production code.

DRY (Don't Repeat Yourself)

If you write the same login sequence in 30 tests, extract it:

# Bad: Repeated in every test

def test_view_profile():

login_page.navigate()

login_page.login("user@example.com", "password")

# ... test logic

# Good: Fixture handles authentication

@pytest.fixture

def authenticated_user(login_page):

login_page.navigate()

login_page.login("user@example.com", "password")

yield

def test_view_profile(authenticated_user):

# User already logged in

# ... test logicSingle Responsibility

Each method should do one thing. Don't create login_and_purchase_item() that does everything. Separate concerns: login() handles authentication, purchase_item() handles shopping.

Descriptive Naming

Names should reveal intent. test_1() is useless. test_successful_login_redirects_to_dashboard() documents behavior.

When POM Helps (And When It's Overkill)

Page Object Model isn't always the right choice.

POM Excels When:

You have multiple tests for the same pages: If ten tests interact with the login page, POM centralizes those interactions.

UI changes frequently: Design iterations, A/B tests, rebranding, POM absorbs these changes in page objects instead of breaking every test.

Multiple team members write tests: POM provides consistent patterns. New team members follow existing page objects instead of inventing their own selector strategies.

You test complex workflows: Multi-step processes (checkout, onboarding, multi-page forms) benefit from organized page objects that chain together.

POM is Overkill When:

You have five simple tests: Writing elaborate page objects for a tiny test suite adds complexity without benefit. Start simple. Refactor when duplication emerges.

You're prototyping or exploring: Early in a project, you're still learning the application. Premature abstraction locks you into patterns before you understand the problem.

The UI is unstable: If the application changes daily and tests are experimental, POM won't save you. Wait until the UI stabilizes.

You're testing APIs or backend logic: POM is for UI testing. API tests and unit tests have different patterns.

From Chaos to Clarity

A company had 400 automated tests maintained by three QA engineers. Every sprint included "Test Maintenance Week" where they updated broken tests. New features were delayed because "tests aren't ready yet."

They refactored to Page Object Model over six weeks. At the end:

One UI change used to break 50+ tests. After POM: the same change required updating one page object method. Twenty tests passed immediately.

Test maintenance consumed 30% of QA time. After POM: 5%. QA engineers started writing new tests instead of fixing broken ones.

New QA hires took weeks to write tests. After POM: they followed existing page object patterns and contributed tests their first week.

The architecture change didn't just fix tests. It changed how the team viewed test automation, from liability to asset.

Next Steps

You now understand Page Object Model architecture. You've seen working examples in Python and TypeScript. You know when to apply these patterns and when simpler approaches work better.

For a complete POM project template with working code, see our GitHub repository (includes pytest and Playwright examples, CI/CD configuration, and best practices documentation).

If you're building test automation from scratch, review Chapter 3: Test Automation Frameworks and Chapter 4: Implementation Guide to understand the full picture.

If you're tired of maintaining brittle tests altogether, Autonoma's AI self-healing handles selector changes automatically so POM becomes optional, not mandatory.

The best test automation architecture is the one you'll actually maintain. Page Object Model gives you that foundation, or you can let AI handle the brittle parts entirely.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Page Object Model only for Selenium?

No. POM is a design pattern, not tool-specific. It works with Selenium, Playwright, Cypress, Puppeteer, or any UI automation framework. The pattern, encapsulating page interactions in classes, applies regardless of the underlying tool.

Should every page have its own page object?

Not necessarily. Create page objects for pages you test frequently. If you test a page once, a page object might be unnecessary overhead. Start with high-traffic pages (login, checkout, search) and add page objects as patterns emerge.

Should page objects contain assertions?

Generally, no. Page objects should expose state (is_error_displayed(), get_username()) but tests should contain assertions. This keeps page objects reusable, different tests might assert different things about the same page state.

How granular should page object methods be?

Balance granularity with usability. Very granular methods give flexibility but verbose tests. Coarse methods are convenient but less flexible. Provide both: high-level methods for common flows and granular methods for edge cases.

Should I use POM with AI testing tools?

AI tools like Autonoma use intent recognition instead of brittle selectors, which reduces the maintenance burden POM addresses. If you're using AI self-healing, POM becomes optional, the AI handles selector changes automatically. However, POM still helps organize complex test suites and makes tests more readable even with AI tools.

How do I refactor existing tests to use POM?

Start small. Pick your most brittle page (usually login or search). Create a page object for it. Refactor tests using that page one by one. Once you see the benefits, gradually expand. Don't try to refactor 400 tests in one go, incremental improvements compound.

What about mobile testing?

POM works for mobile testing too. You might have separate page objects for mobile vs desktop if the UI differs significantly, or use conditional logic within page objects to handle responsive behavior.

What's the difference between POM and Screenplay Pattern?

Page Object Model focuses on pages and their elements. Screenplay Pattern focuses on actors, tasks, and interactions, it's more behavior-driven. POM is simpler and more widely adopted. Screenplay is more expressive but has a steeper learning curve. For most teams, POM is sufficient.

Course Navigation

Chapter 5 of 8: Page Object Model & Test Architecture ✓

Next Chapter →

Chapter 6: How to Reduce Test Flakiness

Flaky tests are the #1 reason teams abandon automation. Learn root causes and battle-tested techniques to fix them. Reduce flakiness to <1% with dynamic waits, test IDs, and proper isolation.

← Previous Chapter

Chapter 4: Test Automation Frameworks Guide - Compare Playwright, Selenium, Cypress, and Appium